INTERVIEW BY ROXANNE OUELLET-BERNIER

“Table for one,” says the young man staring at his reflection in the bathroom mirror. Wearing nothing but a pair of unbuttoned trousers and a carefully stained shirt, he slips into bed to enjoy a meal accompanied by his intimacy.

In an era of forced stillness Raphaël Viens's graduate collection, aptly named, Table for One, seems to come at a providential time, exploring with great self-awareness the reality of living alone. Reflecting on his own experience and background, he develops a fascination towards the art of the table and the idea revolving around the ceremony of eating, from its etiquette to its unconscious mannerism.

Coming from a not-so-academic background, Viens chooses to study fashion design on an impulse to explore and broaden his perspective on design. If by the time he started his BA at L’École supérieure de mode de l’ESG UQAM, he did not have the same certainty towards actually making clothes, he was inspired by the very conceptual approach of his professors who made him see the possibility of design outside the often superficiality of fashion. “I was really motivated by the approach of our first-year design teacher, and I came to realize that fashion could in fact be political and bring us to a reflection,” says Viens. For almost a year, he delved into this approach, reflecting on the impact his garments could have on society, to then acknowledging his appreciation for menswear from its certain rigidity to its tradition. “I did not feel like filling a void anymore. I wanted to explore what I knew very well in the way I dress and then bend its rules,” he says. For his second-year collection, he studied the formality of menswear, analyzing its silhouette and the key elements of tailoring, all while keeping a certain nostalgia, thoughtfully infused in his sensibility.

During his internship with Emile Racine - where he learned the fundamentals of shoemaking – Viens was already in the early stages of the ideation of his graduate collection. Somewhat uncommonly, the name of his collection, Table for One, came first and the rest emerged from this idea. “At first, it revolved mostly around the concept of a table for one person, or how you would adapt a table for a single patron in a restaurant,” adds Viens. From then on, he deepened his research by reading about modern solitude and masculine intimacy. He found enlightenment in the writing of Edward T. Hall, The Hidden Dimension, where, in the 60s, he goes through his perception of what future societies might look like as the automobile is in full exponentiation and how it drives humans to isolate from one another. Viens then followed with the fictional work The Extra Man by Jonathan Ames, which relates the life of a man who explores his own identity and intimacy through cross-dressing. He says “The protagonist’s relationship with the garment was, in a way, almost intimate. He would take time to describe his perception of it, its texture, the way it fell, going to the extent of analyzing what other people wore. Most of the time it was a bit sexual, but I liked this facet of the masculine intimacy, and how it interlaced with the feminine intimacy.”

Lastly, Viens collected relevant passages from the magazine What Men Wear, an oral history of male dressing in the 21st century. It investigates the insand- outs of men’s wardrobe habits and delves into their relationships with their garments. From these notes, he wanted to understand and broaden his perspective of menswear and how men dress while keeping in mind his preferences and attitude.

However, Table for One goes much further than analyzing the relationship between men and their attire. It is, first and foremost, an exploration into the somewhat intimate act of having a meal, in this case, in one's own company. For him, the concept also comes from a certain fascination he has always entertained towards the simple act of eating. “It’s not solely an appreciation of food itself, it revolves mostly around the procession of eating, of setting the table and choosing the appropriate silverware,” adds Viens. Even if he lives alone, he has always preferred eating at the table and he remains slightly intrigued by the antics of his family who have always favoured the living room instead of the dining room. As Viens wanted to further his understanding of such practice, he began asking his entourage what their habits were, but also on how they would set the mood, and if they had a certain attire they preferred. As the answers would vary considerably, it inspired him in creating a collection for any inclinations, with garments that would accommodate many settings. In a sense, his intentions remain mostly focused on faithfully grasping the specifics of this intimate moment, and on how this behaviour tends to change when one is on its own.

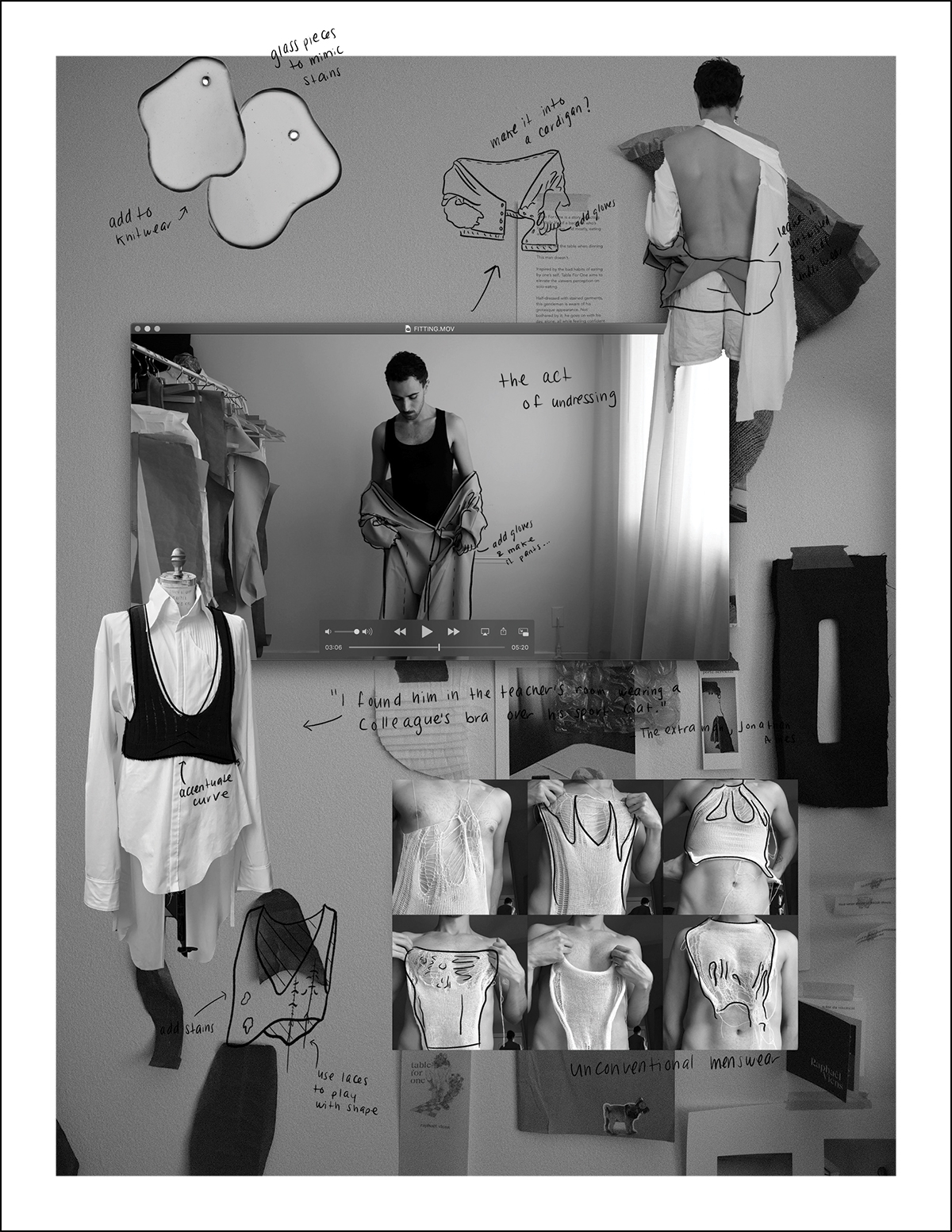

From its first preliminary drafts, his collection already had a unique standpoint on male intimacy, playfully bringing the art of the table to the often rigidity of menswear. Using classic tailoring pieces, he plays with their proportion, giving it a sometimes-undressed appeal, while hinting at a more feminine wardrobe. As the confinement allowed him to experiment with a knitting machine, he developed delicate, yet intricate, garments that were inspired by vintage underwear. These added pieces give an extra dimension to the more sober tailoring wool he has chosen, all the while reinforcing the comfortable intimacy of being home alone. As for the art of the table aspect, Viens brings it in his garments in subtle yet clever references, with hems matching the rim of a favoured serving tray, or with simply rounder lines to the slight hardness of the tailoring pieces, evoking the shape of amber glass vases. The looks are all brought in together with delicate glass pieces made for him by a Montreal artist. This refers to a certain appreciation to the late 60s and 70s, while silver and brass notes are used as an acute allusion to the silverware sets his grandparents had.

But what stands out the most in his research for Table for One is his innate aptness in creating perfect scenery, where his garments inhabit the space in the utmost natural way. It gives his documentation a defined personal touch. In his small apartment, the shelves are lined with glassware and ceramics, and it somehow becomes the perfect playground for his experimentations. “I really take the time to film my pieces, seeing how the colours, textures and silhouettes interact with one another. When I create those settings, it also helps me to visualize the final product, on how I will style them and shoot them. Photography is definitely what inspires me the most in my process,” he adds. From these séances, Viens was inspired to create the accessories that would epitomize the concept of his collection and bring every look together like part of the same film. If the garments are more about the sense of comfort and intimacy, the unconscious mannerism and ritual of eating alone are all carefully brought in together with these pieces, all-referring to the slight pragmatism of décor pieces.

“With my accessories, I wanted to represent the act itself, really thinking about what one would need to eat anywhere he wishes. I created a stiff leather placemat that can be styled as a bag, but that allows you to eat on yourself. In the middle, there is a slightly sunken area where a plate would fit perfectly, paired with small pockets for cutlery. I’ve also created a bag in the shape of a carafe and the majority of the silhouettes are paired with gloves, in the idea of keeping the hands clean through the process of eating in bed, maybe,” he says.

As the mise-en-scène is so carefully brought together with the garments and accessories, Viens also met with a Montreal-based visual artist, with whom he collaborated in capturing the lived-in aspect of his collection. They worked on creating a print, a contemporary interpretation of a Toile de Jouy, where six different scenes would take place. While keeping some of its precepts like the subdued colour palette, the usual pastoral scenes are now moved into walls, where a diversity of men are represented alone at home, in carefully furnished scenes. As for the art of the table, it is playfully illustrated throughout the toile, where food, drinks and dinnerware complete each of these settings.